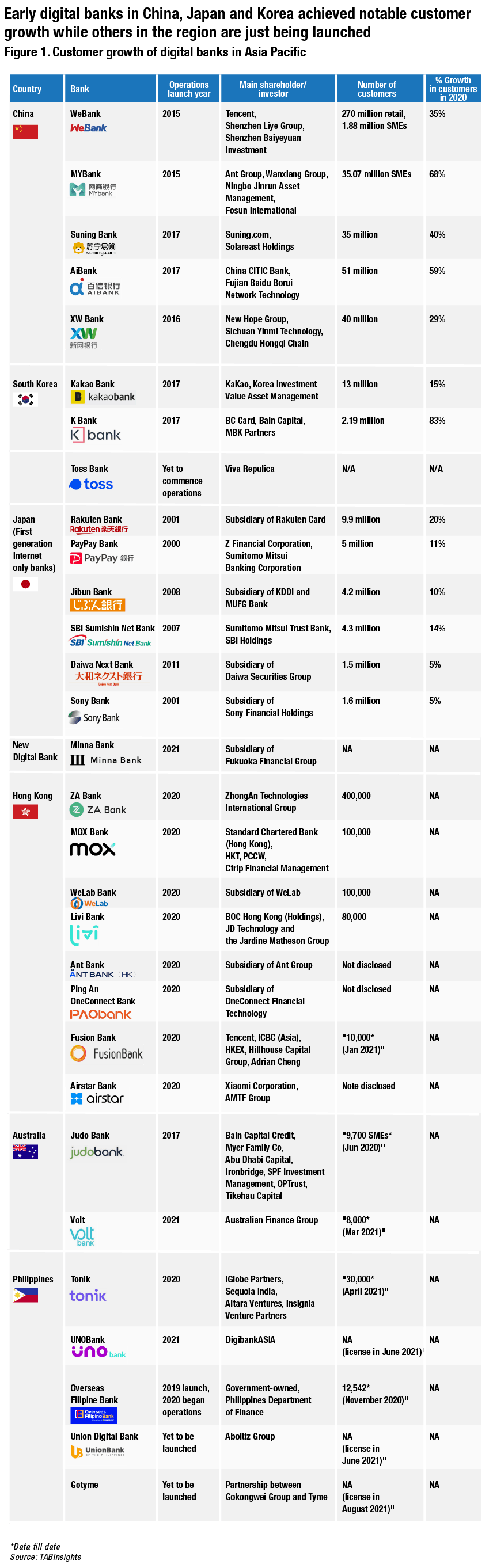

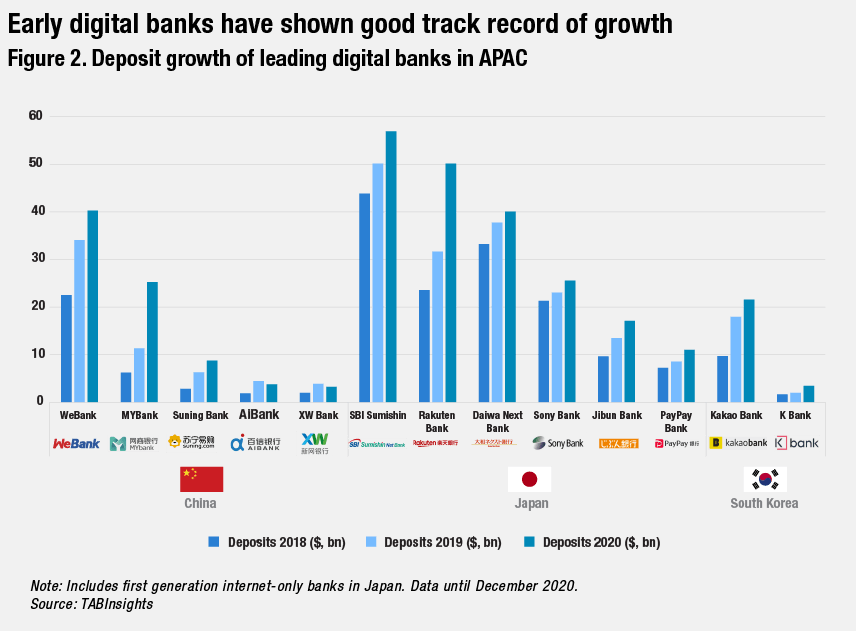

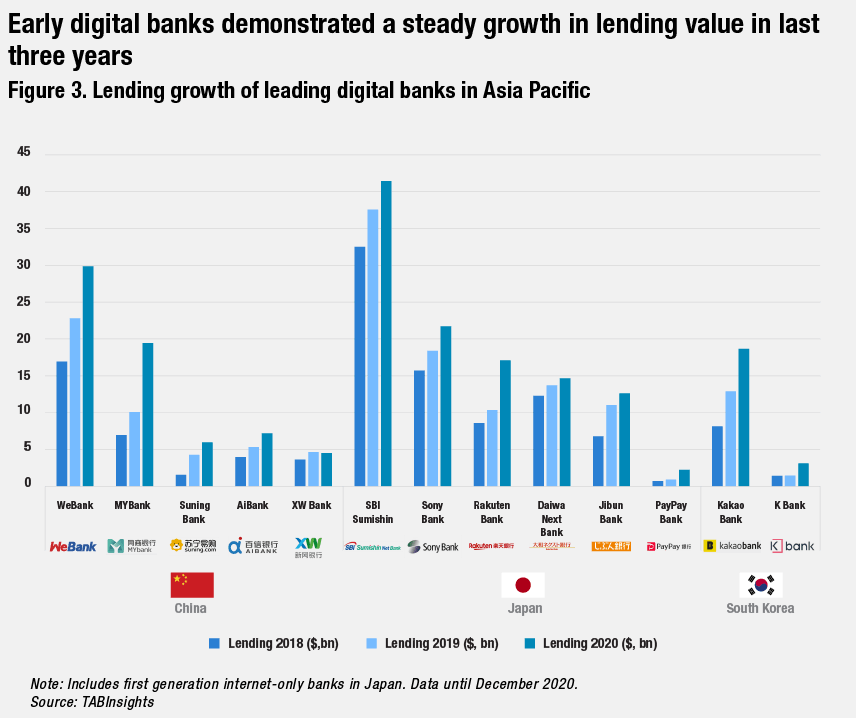

- Early digital banks achieved notable growth in mainland China, Japan and South Korea compared with the rest of APAC

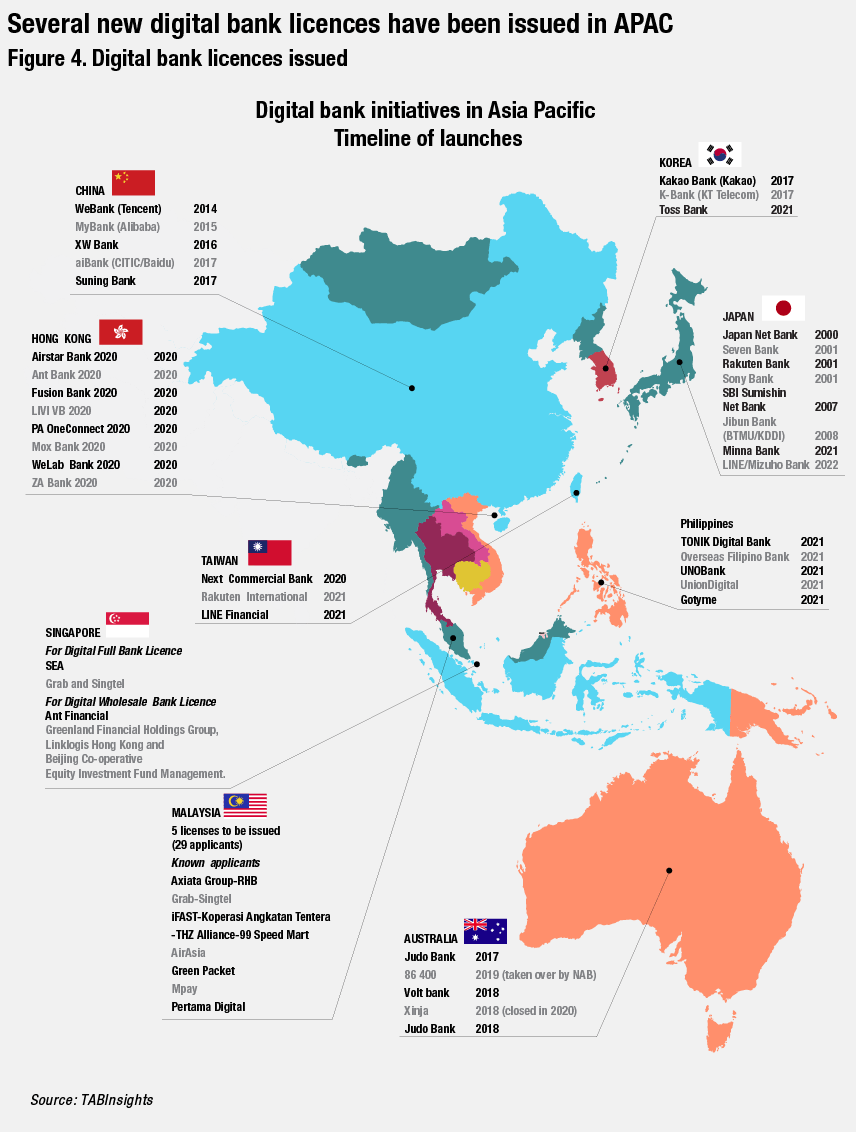

- Regulators continue to issue new digital bank licences in the region

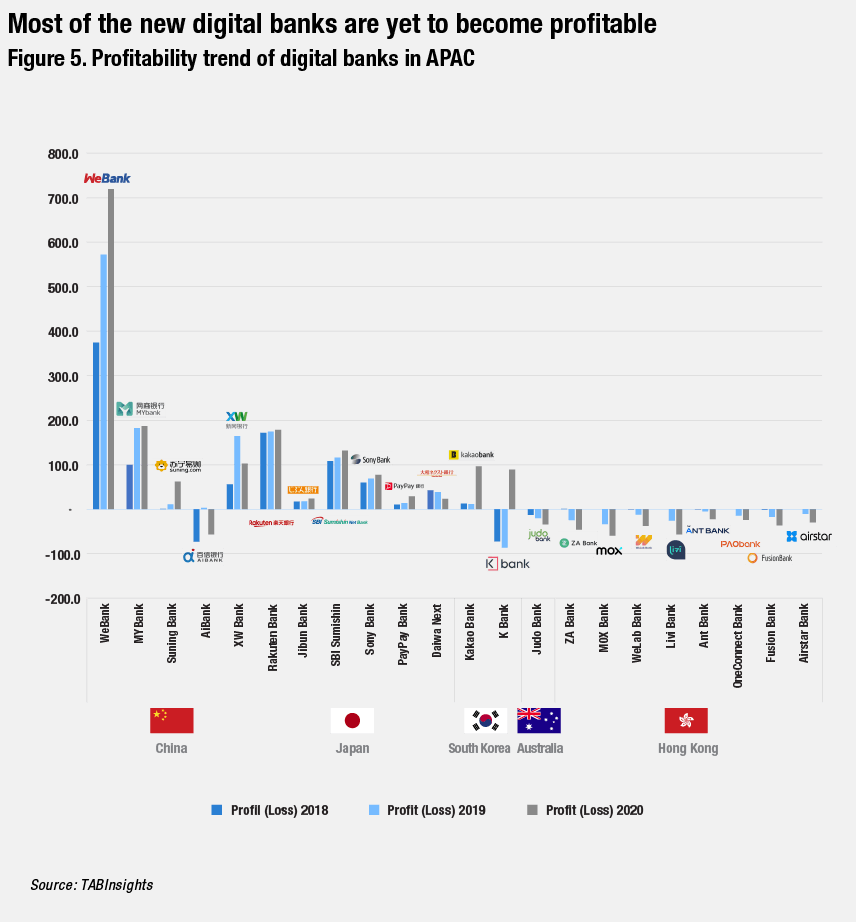

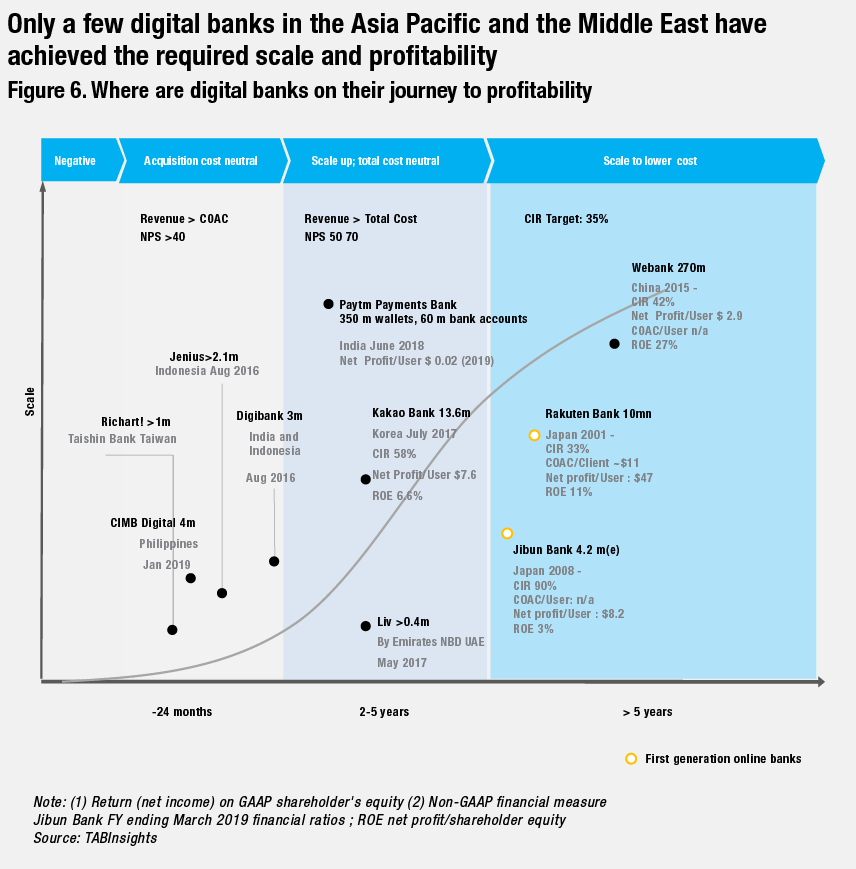

- Most new digital banks have yet to achieve the requisite scale and profitability

Recent spurt in the growth of digital banks is shaking up the dynamics of the financial industry in Asia Pacific (APAC) as new licences are being issued by regulators across the region. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated customer appetite and growth of these digital banks as well as the digital transformation initiatives of the incumbents, heating up the competition.

Digital banks aim to focus on the evolving customer needs and pain points through a completely digital, agile and operationally efficient model, as well as an intelligent service. Their primary target are digital-savvy customers, often in niche market segments, especially in the white spaces unaddressed by traditional institutions. Technology is undoubtedly their biggest enabler as most of them build their technology stack from scratch, and are cloud native and cost effective compared with incumbents that are often saddled with complex legacy technology. Furthermore, they focus on scale through faster ecosystem collaborations.

However, many of these neobanks are quite early in their journey, far from achieving the requisite scale for sustainable profitability. Meanwhile, incumbents are rapidly digitising their operations, leveraging them across multiple business lines and deepening customer base to expand customer reach. The competition is getting fiercer, and it is now a race against time.

Evolving trends in digital banks in APAC

Digital banks in the region can be broadly characterised into three different models. Firstly, most prominent among these are the regulator-licensed independent digital banks such as WeBank, Judo Bank and ZA Bank. Secondly, there are digital entities formed by a partnership between a non-bank digital or fintech player with a banking partner, for example LINE Bank in Thailand. Thirdly, there are digital subsidiaries of an existing bank, for example Digibank by DBS and Jenius by Bank BTPN.

The first generation online banks in Japan, followed by early digital banks in mainland China and South Korea, emerged as innovators and differentiators in the region, witnessing notable growth.

Since 2014, mainland China has issued five digital bank licences. Among these, Tencent-owned WeBank now has 270 million retail and 1.88 million small and micro business customers. It successfully leveraged its parent company’s technology and market presence to achieve strong customer growth and profitability. Ant Group-backed MyBank serves 35.07 million small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), a growth of 70% over last year.

Xiaomi-backed XW Bank is another example and has acquired 40 million customers. Being backed by a strong parent consortium is one of key enablers for these banks to scale rapidly. However, the regulatory supervision for fintech and these digital propositions are increasing in the country. For instance, XW Bank was reprimanded by the regulator earlier this year for charging higher interest rates and for failing to follow risk assessment and debt collection regulations.

Among other early digital banks in the region, South Korea’s Kakaobank leads with over 13 million customers. In Japan, online banks have commenced operations since 2001. Among these, Rakuten Bank became the first bank to reach close to 10 million accounts.

Recognising the value of these digital propositions in enabling financial inclusion and customer service, governments in several markets have raced to issue new digital bank licences. Leading among these are Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Philippines. Many applicants for these licences are backed by consortiums led by existing financial players.

Some of these new digital banks have recently become operational. It will be a challenging and long and winding journey for them to achieve sustainable profitability.

These neobanks are often pressed for resources and funding to scale with speed. Furthermore, the competition is continually increasing as new banks enter the market and the advantage of differentiation is eroding. Meanwhile, the incumbents are undertaking rapid digital transformation to maintain their lead and innovate their own services. It can be challenging to convince customers to switch banks unless these new banks can maintain their competitive differentiation.

In the UK, despite launching four years ago, many digital banks continue to make losses. Starling Bank, which provides business-to-business banking and payments services through banking as a service (BaaS), claims to be the first bank to break even last year. On the other hand, banks such as Revolut, with 16 million customers, are ahead in customer reach but still not profitable.

Meanwhile in APAC, excluding mainland China, South Korea and Japan, most digital banks are just starting their operations and have yet to reach the critical mass to achieve sustainable profits. These banks are likely to need strong funding support in the initial years. Thus, not every bank will be successful. In Australia, two neobanks have already exited.

Australia: Digital banks target niche segments amid challenges

Dominated by four large financial institutions, Australia remains a challenging market for digital banks. The recent failure of Xinja and takeover of 86 400 demonstrate this.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) gave licences to four digital banks – Xinja, Volt Bank, 86 400 and Judo Bank – in 2019. The fledgling sector suffered a setback with the exit of two of these. Xinja closed and surrendered its licence in December 2020, blaming the COVID-19 pandemic and challenges in raising investor funds. Xinja was the most popular neobank, having gathered $200 million customer deposits within a month after the launch because of its high-yield savings account. Sustaining this high-cost business model became a challenge for the bank as its funding dried up.

In January 2021, 86 400 announced that it was being acquired by National Australia Bank (NAB). It had over 85,000 customers, AUD 375 million ($271 million) deposits and 2,500 accredited brokers. NAB acquired 86 400 reportedly to accelerate the growth of its own digital bank, UBank.

Now, two fully licensed digital banks remain – Judo and Volt. Judo received its licence in 2019. It is targeting SMEs, with its loan book increasing to AUD 1.8 billion ($1.3 billion) in fiscal year (FY) 2020, while deposits increased to AUD 1.4 billion ($1 billion). It raised $284 million in its fourth round of funding early this year.

Meanwhile, Volt has adopted the route of BaaS. It recently entered a partnership with UK-based BaaS provider Railsbank. This will provide Volt access to Railsbank’s global network of partners and customers and enable companies to launch financial products in Australia within their own customer experience. It is yet to launch some of its products.

Steve Weston, CEO at Volt, shared, “We have 50,000 people who have expressed interest, of these we invited 8,000 and all opened up bank accounts. We have just under AUD 90 million ($69.7 million) deposited with those accounts. It didn’t make sense for us to go and launch deposits to the public because until we begin lending, we only deposit money with different banks at a lower interest rate. We have recently commenced mortgage lending, so now is the time for us to bring more customers and partners with Railsbank”.

He added, “We will finish the proof of concept in the next few months, and then we'll launch to the public our additional products, deposits and features. We will go from mortgages to personal loans and then ultimately into SME lending, but it will be done in a very disciplined way”.

Weston feels that BaaS is a relatively less contested market, wherein he anticipates a lower cost of acquisition via partners. BaaS is a collaborative model wherein the bank provides the banking and compliance services while fintech (and businesses) use their ecosystem to offer embedded finance to their customers. Companies often aim for stronger customer retention, new revenue streams and wider data on the payment behaviour of users.

Justin Xiao, chief operating officer at Railsbank, Asia Pacific, commented, “We're making it easier for fintech to lift and shift their services across regions. This is what we are doing with Volt Bank in Australia. When they want to prototype, launch and scale, they are able to work on our platform”.

The newest addition among digital banks in Australia is Alex Bank, which launched its retail lending business in July 2020 and was granted a restricted authorised deposit-taking institution licence by APRA in July 2021. Alex uses cloud-based technology and is focused on the white space opportunity in consumer finance where banks have traditionally underinvested.

“It is quite a lonely space”, commented Simon Breitz, CEO and co-founder at Alex Bank. “We are a lending-led neobank. We have built a lending product where customers can apply in three minutes. We have Alex intelligence for decision deals for a customer within seconds, and we can fund within a couple of hours. So that's extremely fast compared to legacy banks here in Australia,” he explained.

So far, Alex Bank only has a few hundred customers and an AUD 8 million ($5.7 million) loan book. Breitz hopes to scale within the next 12 months, with a target of AUD 100 million ($ 71.3 million).

Given the Australian market dynamics, growing competition and the need to scale with speed, it will be a challenging journey for these neobanks, though there remains potential of growth in niche segments untapped by traditional players.

Hong Kong: New digital banks have become operational but have yet to scale

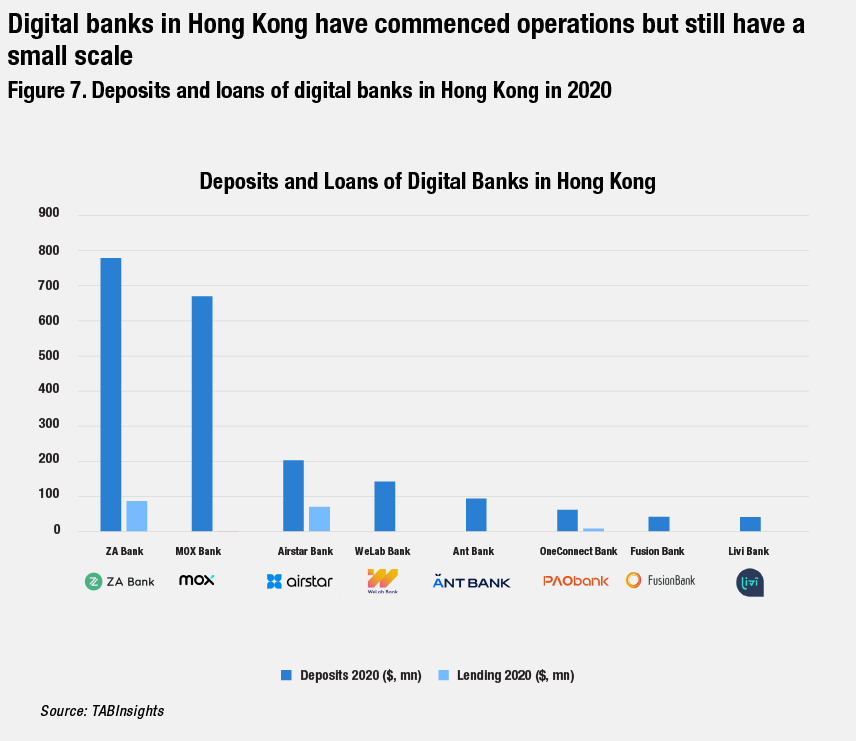

Digital banking in Hong Kong is getting crowded as the newly licensed digital banks become operational. Hong Kong Monetary Authority handed licences to eight digital banks in 2019, many of which are backed by financial powerhouses.

These include Fusion Bank led by Tencent and ICBC, Mox by Standard Chartered, Ant Bank by Ant Group, livi bank by Bank of China, ZA Bank by ZhongAn Technologies, Airstar Bank backed by Xiaomi and AMTD, OneConnect Bank by Ping An Bank, and WeLab Bank.

The leading among these is ZA Bank, which acquired 400,000 customers by July 2021. It commenced operations in the first quarter of 2020, initially luring customers with an offer of a high return on deposits. Over the year, it has expanded to offer a range of products across loans, deposits, business banking, cards, and insurance.

Cloud-based technology, cost-efficient digital processes and ecosystem partnerships are key enablers for most of these new banks. WeLab Bank is multi-cloud based and acquired 100,000 customers. Standard Chartered-backed MOX also crossed 100,000 customers. It has partnership with Hong Kong’s telecom, media and digital solutions providers, such as HKT, PCCW Group and Ctrip, which brings advantage of access to its partners’ customer base.

Livi bank established itself as a virtual banking partner for yuu, a rewards club that partners with 2,000 outlets. Over 50% of livi bank’s customers have now linked their yuu accounts to the livi app. The bank recently launched a buy now, pay later service and plans to add wealth management products in the future.

“Our customer numbers reached 80,000 with total deposits of HKD 900 million ($115.7 million). Sixty percent of our customers have activated the UnionPay QR Payment on the livi app and about half of our customers are livi debit Mastercard holders,” shared David Sun, CEO of livi bank.

As these digital banks step into their second year of operations, they seek to expand their products. Mox Bank launched its credit card, Airstar bank launched corporate banking and ZA bank added insurance to its portfolio.

Talking about his future plans, Sun commented, “We will launch products and services that meet the everyday needs of Hong Kong consumers, as well as wealth management services that help people meet their longer-term goals in education, health and financial security. We are also working with different businesses to develop our ecosystem for our customers”.

However, most of these banks are still far from profitability and is currently bleeding cash. As of December 2020, Mox Bank reported a loss of HKD 456 ($58 million), livi reported a loss of HKD 438 million ($56 million), and ZA Bank had a loss of HKD 352 million ($45 million).

The market’s confidence in the sector was also dented when Xiaomi’s CEO Lei Jun resigned recently as the chairman at Airstar Bank, saying that he wanted to focus on other operations of Xiaomi. This came after the bank announced a HKD 232 million ($30 million) loss.

Philippines: New digital bank licences issued

The Philippines grapples with a significantly low financial inclusion, with a 70% unbanked population. While 69% of its adult population have access to mobile phones and 53% use the internet, less than 10% use these for financial transaction. Regulator Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has now set the target of digitalisation of 50% of the country’s retail transactions and financial inclusion of 70% of Filipino adults by 2023. The BSP has also paved way for the entry of new digital banks that disrupt traditional models with attractive customer offers and lower operating costs.

Given the market characteristics, digital banks could play a significant role in the Philippines. The regulator has approved the applications of five digital banks – Overseas Filipino Bank, two neobanks Tonik Bank and UNO Bank, Union Digital Bank, which is the digital arm of Union Bank of the Philippines, and GOtyme, which is backed by fintech Tyme and Gokongwei Group.

The first among them to commence operations is Tonik Bank, which secured over $20 million in retail deposits within the first month of operation earlier this year. The bank is targeting customer pain points and financial inclusion. The bank had reached 30,000 customers by April 2021.

“We are a bank born in cloud with zero on-premise infrastructure for customers. It is built on multi-cloud strategy”, said Arivuvel Ramu, CEO of Tonik Bank.

“I want to design a bank which is mobile only, has fast onboarding, higher interest rate, no fee, easy to move money, and localised and hyper-personalised product. We have focused on these in building our technology and agile development process,” he shared.

The other digital bank to commence operations is Overseas Filipino Bank, which launched in the third quarter last year and acquired 12,000 customers within the first 100 days.

Meanwhile, BSP plans to stop accepting more digital bank applications and intends to cap this sector to seven players for better monitoring. It is currently completing evaluation of all current applicants.

Vietnam: Digital banks emerge as offshoots of existing financial players

Vietnam is also uniquely positioned, offering favourable factors for growth of digital banks. With 31% banking penetration, it is severely underbanked but has a smartphone penetration of over 60%. Most of the country’s digital banking propositions are backed by existing financial institutions.

Timo, one of the first digital banks in the country, commenced operations in 2016. The bank partnered with Viet Capital Bank and now has 300,000 customers. Other new digital banks include VP Bank’s YOLO, Maritime Bank’s TNEX, and FE Credit’s UBank.

These banks focus on competitive differentiation through agile technology. TNEX Bank for instance was able to build its infrastructure end-to-end within nine months, from core to front. It is cloud-native, and application programming interface (API) and data driven, with low cost of ownership.

“You can't use old keys to open new doors”, commented Bryan Carroll, CEO and founder of TNEX. “We’re going beyond banking. In our platform, we want banking to be invisible and the experience to be upfront. Our ecosystem is made up of four platforms. We have a financial platform, a social platform, where you can chat with people in-app, you can talk to friends. We have a wellness platform and we're building this up because that ties into our fourth platform, which is our marketplace, our ecosystem of merchants. It’s all about experience and loyalty. Loyalty will come from embedded financing,” Carroll added.

UBank, a digital proposition by FE credit and VP Bank, also has cloud-based technology and APIs, and is focusing on expanded services to scale.

Talking about their strategic focus, Gunneet Singh, head of product and customer engagement at Ubank, shared, “It has to be value-added service. We are looking to offer lending proposition combined with insurance especially designed and targeted for mass and upper mass segment. This is a complete package of payroll banking solution, combined with lending and insurance. All three are being delivered to the customer digitally now”.

Singapore: Awaiting the launch of licensed digital banks

After evaluating 21 candidates, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) issued four licences in December 2020. The country has the most stringent paid-up capital requirement for digital banks in APAC, at SGD 1.5 billion ($1.1 billion), and required applicants to provide a five-year financial projection of the proposed digital bank with a path towards profitability.

The recipients of two full-digital bank licenses include a consortium from Grab and Singapore Telecommunications, and an entity wholly owned by Sea Limited. Meanwhile, two wholesale digital bank licences were given to Ant Group and a consortium of Greenland Financial, Linklogis, and Beijing Co-operative Equity Investment. They are expected to become operational by 2022.

However, some of these applicants have been facing increased scrutiny. Ant Group has been subject to increased regulatory scrutiny in China over its financial practices and consumer protection issues. Its initial public offering dreams were later shattered last year, and the company was forced to implement multiple changes and restructuring.

Another applicant, Linklogis, a Hong Kong-based fintech, also came under scrutiny recently. It was flagged by Valiant Varriors, a group of activist investors, allegedly for its exposure to real estate, exceeding regulatory limits for commercial factoring, risky third-party transactions, overstated revenue, and the nature of its technology. This report prompted Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing to temporarily halt trading of Linklogis shares. The company later issued a statement refuting the allegations.

Meanwhile, the incumbents are on their own digital tracks. DBS Bank and United Overseas Bank (UOB) have both launched their own digital arms across the region. DBS’s Digibank now has over three million customers in India and Indonesia. While UOB’s TMRW, which launched in Thailand in 2019 and Indonesia in 2020, has 300,000 customers.

Malaysia: Selection of new digital banks continues

Taking cue from its regional counterparts, Malaysia is also currently in the process of evaluating applicants for digital bank licences. Bank Negara Malaysia has developed the regulatory framework and intends to issue five licences. It has received 29 applications early this year.

A mix of banks, industry conglomerates, fintechs, e-commerce players, and technology leaders are among the contenders. Some applicants have disclosed that they are vying for the licences. These include AEON Credit, Axiata-RHB, BigPay, Grab-Singtel, Green Packet, iFast, MPay, Pertama Digital, PUC, and Star Media Group. The details of successful applicants are expected to be announced by the first quarter of 2022.

Retaining competitive edge will be a challenge for newcomers

The competition across the APAC financial landscape has certainly become heated as these new digital banks become operational, riding on competitive differentiation in customer service and higher cost efficiency through use of emerging technologies and data. They must address customer pain points in niche segments and white spaces left behind by incumbents in financial services.

However, retaining this competitive advantage will be a challenge. The incumbents are proactively undertaking accelerated digital transformation, adopting new technologies and innovations to gear up for the fight and maintain their lead. Meanwhile, the regulatory scrutiny of fintech and digital players is also increasing.

New digital banks will need to continually invest in order to retain their competitive advantage, expand their service capabilities rapidly as well as focus on ecosystem development to grow in scale. Given the growing competition and evolving landscape, new digital banks will require a strong funding as they are likely to bleed cash for the initial years before they can show achieve sustainable scale and profits. The long-term winners will be the ones that are built on a truly customer-centric strategy and designed with a sustainable business model enabled by a futuristic technology foundation and agile innovation.